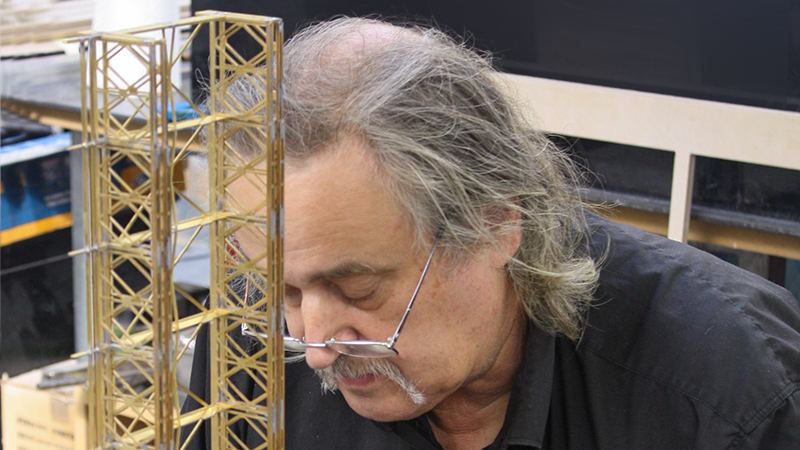

Meet Mike Quarry, one of Amalgam’s engineers working on all sorts of projects. He’s been…

Prototype Plastic Moulding: Vacuum Casting and 3D Printing

A little over twenty years ago, 3D printing or Rapid Prototyping as it was then known, changed the world. The recent explosion of interest in the process is not indicative of a sea change in the industry, but a public awakening to an industrial process that is quick, convenient and downright cool. The science fiction ideal of being able to manifest objects from your computer captures the imagination; could you 3D print a model yacht, a concept design of a yacht, a full-sized working cruiser? Designers, architects and artists have embraced 3D printing and innovative projects are appearing daily.

There are, however, limitations. It is important to remember that 3D printing and all the associated Additive manufacturing technologies, stereolithography, laser sintering, etc. are stages of a greater whole – prototyping. A 3D print is generally a step towards production, not production itself, and while it is tempting to think of a 3D printer as a self-contained factory, this is unwise. Being able to print flexible elastomers and rubberised components, for example, is achievable, but a poor substitute and a corner cut. True some small-run highly specialised components are being produced by laser sintering, both in polymers and metal, and this does offer a unique opportunity to customise items such as replacement joints, surgical implants and prosthetics – but there are exceptions to every rule.

Additive manufacture, for us at Amalgam, is more often just the first stage of the prototyping process. The object is printed as a hard part, cleaned up and finished to texturally replicate the final production object, then cast in a material with physical properties very close to that of the production piece and an all- but identical appearance. Ergonomic flexible components can be created to exacting levels of flexibility, colour and softness. Complex internal structures and unique surface textures can be created, from full gloss, to elegant satin sheens, to a matt injection-moulded spark. A breakdown of our vacuum casting process can be found here. Some of the projects we have undertaken which have involved elastomeric and rubberised elements have included the over-moulded grip and silicon enclosures on the GapGun, the Swimtag Training Aid, and the Avon Bite Valve – all of which have been vacuum cast at striking levels of quality.

Vacuum cast components have properties almost identical to their production counterparts, where they will be used for the most important stages in the design process – trials and testing. A product will either prove its mettle or fail and go back to the drawing board. In some cases, vacuum cast components have ended up being the production parts, since once we have made a mould, many identical casts can be taken from it.

The recent developments in 3D print production are not so much giant leaps of industrial technology, as they are the result of a gradual streamlining, sometimes known as ‘Layman Creep’. As these processes are refined and streamlined to be more cost-effective, and eventually, downright cheap, they begin to graduate into semi-professional circles. In these environments, passionate individuals with no professional constraints have the freedom to play, and that is where ingenuity can blossom – without overheads, budgets and deadlines, users can push the technology in whatever direction they feel, and ‘think outside the box.’ Consequently, there has been a surge in users embracing additive manufacture, designing, making and pushing the limits of this process. But to really push a project forward, after taking your print out of the machine, one must always be asking, ‘what is the next step?’.

Head to our services page for more information on how we use the 3D print process in our work.